Let’s rewind just a little to February 2nd, aka Groundhog Day. Bill Murray and Punxsutawney Phil notwithstanding, this year’s G-Day was distinctly lacking its usual, pleasingly meaningless charm. Instead, the penny dropped on a frightening familiarity as we stared into the abyss of lockdown 3.0 (as 2021-style distancing in London has become non-affectionately known) and a Saturday-looks-just-like-Wednesday time warp the size of Alaska.

But curious things happen in extreme circumstances, and a newfound pre-occupation with the passing of time (specifically, a ton of it) has brought some surprisingly comforting reminders about the nature of design and style. For instance, that there’s a special breed of magic in things that take a long time to create or master. Perfection – true labours of love – rarely come easily, which is just how we like it.

Numerous ground-breaking designs were years (and thousands of prototypes) in the making, often embodying underdog spirit. The first Dyson vacuum apparently blew through 5126 iterations in its 15-year gestation (by #3727 Dyson’s wife Deirdre Hindmarsh was reputedly giving art lessons to raise extra development cash) while the famous Leatherman ‘multi-tool’, predicted to be in production one month, endured a seven year design odyssey to become the ultimate boy scout pen knife. Verner Panton’s cult classic ‘S’ chair, originally considered too radical to be realised, had a wildly tumultuous history; a comeback king of Travolta-like proportions, it ran through 10 prototypes, 15+ manufacturing rejections, a massive hit and then a defect-driven discontinuation before a renaissance in the 1990s. In architecture, see Gaudi’s epic Sagrada Familia: born in 1882, Jordi Fauli and his team are predicted to wrap the project in 2026.

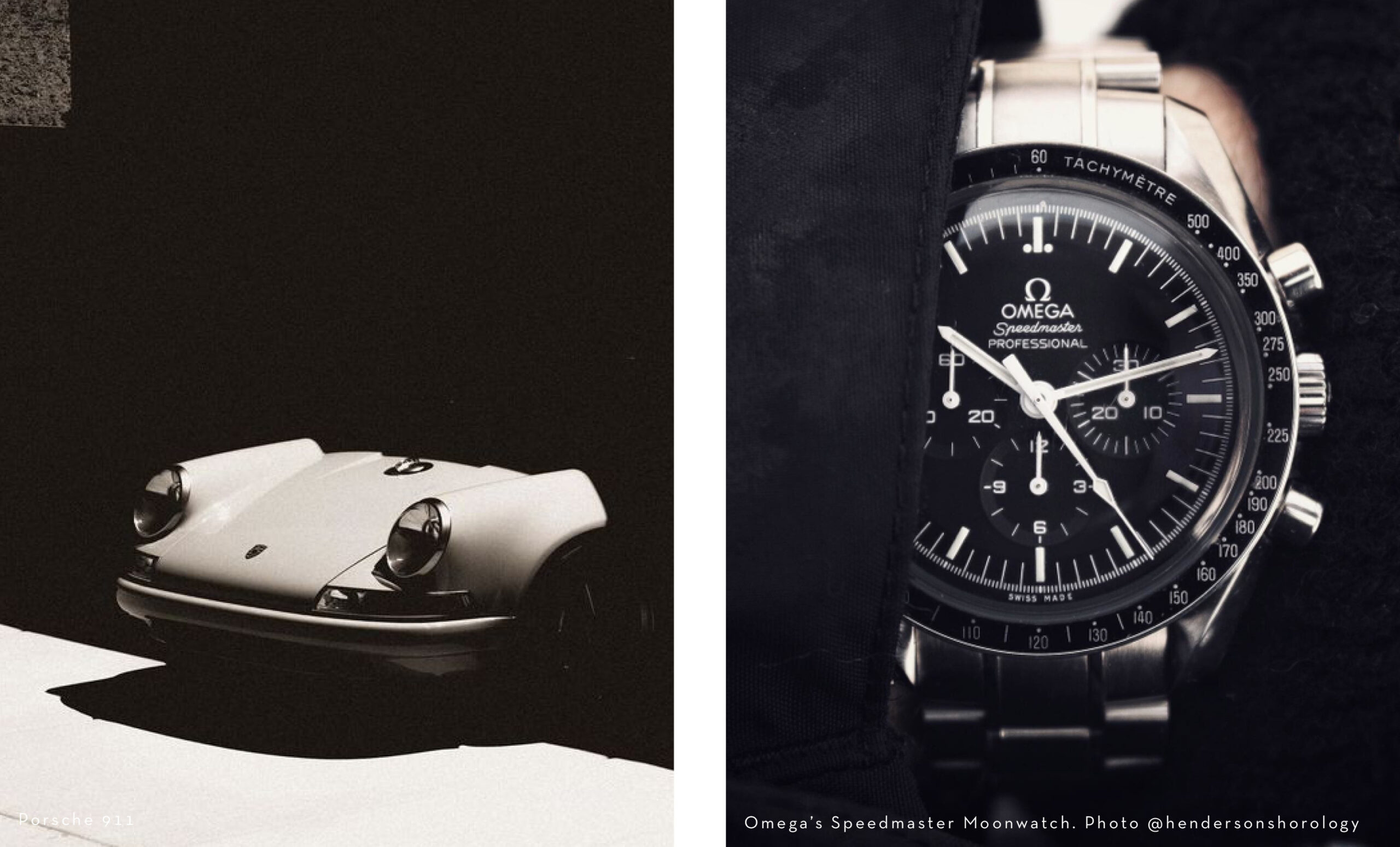

Iconic items religiously remastered have a halo similarly hard to resist. It’s a glow attuned to the Japanese term ‘Kaizen’, meaning ‘change for the better’ or ‘continuous improvement’ (equally applicable to business as artistic creativity) wherein gradual and methodical is as seductive as the original eureka moment. Take the Porsche 911, now in its eighth generation. It’s so revered to almost count as cliché, but a purity in the process – the aura of relentless, behind-the-scenes dedication – always pulls it’s enduringly bulbous silhouette back from the brink. Also see Omega’s 2021 reissue of its ‘Speedmaster Moonwatch’ (a timepiece that accompanied the Apollo 11 astronauts on the 1969 moon landings) with a new movement for precision and anti-magnetism for 21st Century appetites, while Hans J Wegner’s winged chair, the epitome of Scandinavian modernism was actually evolved from his Chinese chair (inspired by ancient furniture).

In fashion, there’s London’s Blackhorse Lane Ateliers – a craft denim brand that uses tailoring techniques to (slowly) reimagine the workwear staple. But there are fewer more satisfying examples than the trench coat for the thrill of seeing nostalgia and newness collide in a clever reboot. Proof that the best revamps pay homage to the original without trampling them underfoot, the design, initially created in 1914 by Aquascutum founder John Emary for the British Army, is still being reworked endlessly into ultra-covetable collabs of tradition-meets-achingly cool (see Mackintosh x Vetements as a prime example) that don’t deviate too far from the classic silhouette.

It’s a breed of ‘tribute design’ which, alongside a belief in an intensive design process, underpins the MULO mantra: it took 5 years to collectively approve our mens sneakers; our new desert boots respectfully update the design devised for British Army officers navigating the sands in Burma; while our very first design mission – reimagining mens espadrilles – birthed a shoe that built on more than 600 years of Catalan heritage. We also boast a shoe-making technique with approximately 100 individually steps – a secret sauce of sorts that reminds us daily how often process makes perfection.